All new treatments have to go through clinical trials.

A trial will try to find out if the new treatment is:

- safe

- free from major side effects

- better than any existing treatments.

People choose to take part in a clinical trial because they want to contribute to finding new ways of treating health problems, or because they may benefit from a new treatment themselves.

There are pros and cons to being involved in a clinical trial. Think about your options carefully and discuss them with a doctor before volunteering.

Clinical trials in the UK

In the UK, research and clinical trials are part of the work of the NHS. The people who do research are likely to be the same doctors and other health professionals who provide treatment.

This research will often take place in hospitals or clinics. Research also takes place in universities and research institutes, in social care services, or in the private sector (for example if it’s undertaken by a drug company).

Legal requirements on how clinical trials should be run

An organisation called the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) needs to review and approve every trial, which must also be approved by local ethics committees.

There are different types of trials, depending on the research methods used, and different stages, or phases, depending on how far research has gone into a new treatment or drug.

All trials have what is called a protocol. This sets out the trial's aims and objectives.

Trials also have rules about who can and cannot join. These are called inclusion and exclusion criteria. Often, for example, if you are pregnant you cannot join a clinical trial.

You can find more information on clinical trials, and on making the decision whether or not to join one, on NHS Choices. The UK Clinical Research Collaboration can also provide you with more information about taking part in a clinical trial.

Current clinical trials for people with HIV

Some key areas of HIV treatment and prevention that are currently being addressed by clinical trials:

- Attacking HIV at different stages of its lifecycle in order to stop or delay it damaging the immune system. This is how anti-HIV drugs in different classes are explored and developed.

- Lessening the side effects of drugs that are currently in use.

- Studying drug interactions.

- Curing other conditions often seen in people with HIV, such as diabetes, hepatitis or tuberculosis.

- Managing treatment and healthy living.

- Preventing HIV – the ongoing attempt to develop a vaccine.

- Development of first long-acting injectable treatment for people living with HIV.

What we’ve learnt so far about HIV from clinical trials

- We know more about choosing anti-HIV drugs and how and when treatment should be taken from the findings of trials.

- The PARTNER study found that people who are taking effective treatment and have an undetectable viral load cannot pass on HIV.

- The PARTNER 2 study reported zero transmissions after almost 800 gay couples had sex more than 77,000 times without condoms. The couples were HIV serodiscordant (one partner positive, one negative) at 75 clinical sites in 14 European countries.

- The Partners PrEP study found that there remains a transmission risk within the first six months of treatment as the HIV positive partner’s viral load takes time to come down.

- The IMPACT trial in England ran until the end of 2020 and aimed to address the outstanding questions about PrEP eligibility, uptake and length of use. NHS England and Public Health England enrolled 24,255 participants at high risk of acquiring HIV; in 2021 it reported that PrEP users in IMPACT had 87% fewer HIV infections than comparable non-users. In 2016, the PROUD trial reported PrEP to have an 86% effectiveness in preventing HIV infection.

- HIV treatment is generally most effective if it consists of three anti-HIV drugs. Clinical trials can help guide the choice of which combination of anti-HIV drugs will work best.

- The current recommendation that everyone with HIV should start treatment regardless of their CD4 count is based on the results of a clinical trial. The START study found that people who waited to start treatment until their CD4 count dropped to 350 (which is when people were previously advised to start) had a much higher chance of developing AIDS-related illnesses such as cancers.

- Having a break from HIV treatment makes people more likely to become unwell, compared to people who stay on treatment all the time (the SMART trial).

- A 1994 trial called ACTG 076 found that Zidovudine treatment during pregnancy, labour and the baby’s first weeks of life can reduce the risk of HIV transmission from mother to child by two-thirds. This was groundbreaking at the time.

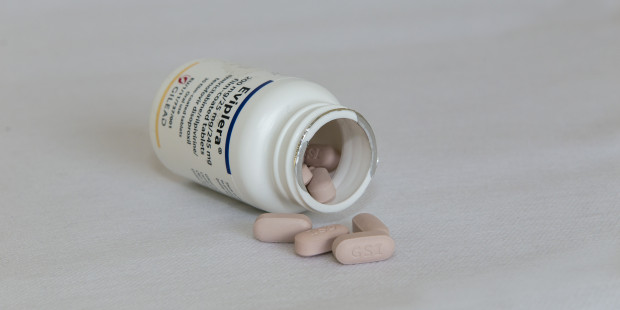

- Following three recent studies in the US focused on reducing toxicity and the drug burden, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the use of a new dual therapy in HIV antiretroviral treatment. The European Commision approved the new drug combination in May 2018. The new drug regimen reduces the number of drugs to two, a single pill combining dolutegravir and rilpivirine.

- The APPROACH study to find a prophylactic HIV-1 vaccine has moved into a human efficacy trial in sub-Saharan Africa, with projected enrolment of 2,600 healthy, HIV-positive women.

Clinical trials have also shown how to best manage other conditions that are common in patients with HIV, such as hepatitis.

How to join a clinical trial

Staff at your HIV clinic may know about trials that are being carried out.

There are also several registers, or lists, of trials going on at any time. You could ask at your clinic about these.

UK CAB, an HIV advocacy organisation, also has information on how to find clinical trials and has listings of current trials.

If you hear of or read about a trial that interests you, the first step is to talk to the trial's contact person.

If you’re currently receiving treatment at a different clinic or hospital from where the trial is being carried out, you might still be able to enrol in it. But you should be sure to tell your regular doctor if you do join a trial at a different centre.

Reasons to join a clinical trial:

- You’ll have access to new drugs, or to new forms of treatment, which may be more effective than existing ones.

- You’ll get more frequent monitoring and access to the most advanced tests.

- The findings of the research may benefit other people with HIV.

- You may receive a small payment, although this is not very common – sometimes patients receive cash compensation or travel expenses for participating in a study.

Reasons not to join a clinical trial:

- The outcome or effectiveness of the trial is not yet known.

- You’re already on effective treatment that you have no issues with.

- You don't want to take the chance of being given a placebo (a ‘dummy’ pill, usually made of sugar).

- Most trials involve many hospital or clinic appointments.

- The pill-taking timetable, or restrictions on your daily life, might feel unmanageable.

- There’s a possibility of unknown or unpredictable side-effects.

- You’re pregnant, or want to be, or don't want to use contraception (if required by the study).

More information about clinical trials

You can find more information on clinical trials, and on deciding whether or not to join one, at UK CAB, on the NHS Choices website and in resources provided by the UK Clinical Research Collaboration.