I was diagnosed at the Middlesex Hospital in October 1982, with what was then called HTLV-III, with the registration L1, marking me as the very first HIV patient at that hospital. I was 33, and that moment felt like being handed a death sentence. The doctors told me there was no cure, and that I had just months to live.

That fear spiralled into hopelessness. In December of that year, I attempted suicide. But in that darkness, my mother’s voice echoed in my mind, 'You must clean up your own mess.' Her words anchored me, and somehow, I chose life.

In 1986, the UK’s Don’t Die of Ignorance campaign was the first campaign to reach every household about AIDS. The media twisted the facts and painted HIV/AIDS as a 'gay plague,' as if we’d done it to ourselves through our 'sexual antics.' That messaging created a “them-and-us” mentality that scarred me deep.

With hundreds of people dying every week, there was a lot of despair. There was no safety net. No help. No accurate information. That began to change when friends of Terry Higgins, the first named person to die of an AIDS-related illness, established the Terrence Higgins Trust in 1982.

I found sanctuary at Lighthouse South London, a drop-in centre for people living with HIV, run by Terrence Higgins Trust in Waterloo. There, you didn’t just get leaflets, you got real support: housing advice, peer counselling, companionship, the works. I was soon asked if I wanted to volunteer, and I volunteered as a receptionist. I greeted people, and offered them a sense of belonging I’d once so desperately craved. It was one of the most fulfilling roles I ever held.

Volunteering was more than community service, it was like healing. When I smiled and introduced myself on reception, I could put people at ease, because there was hope about living with HIV for so long. To make them feel welcome: that mattered deeply.

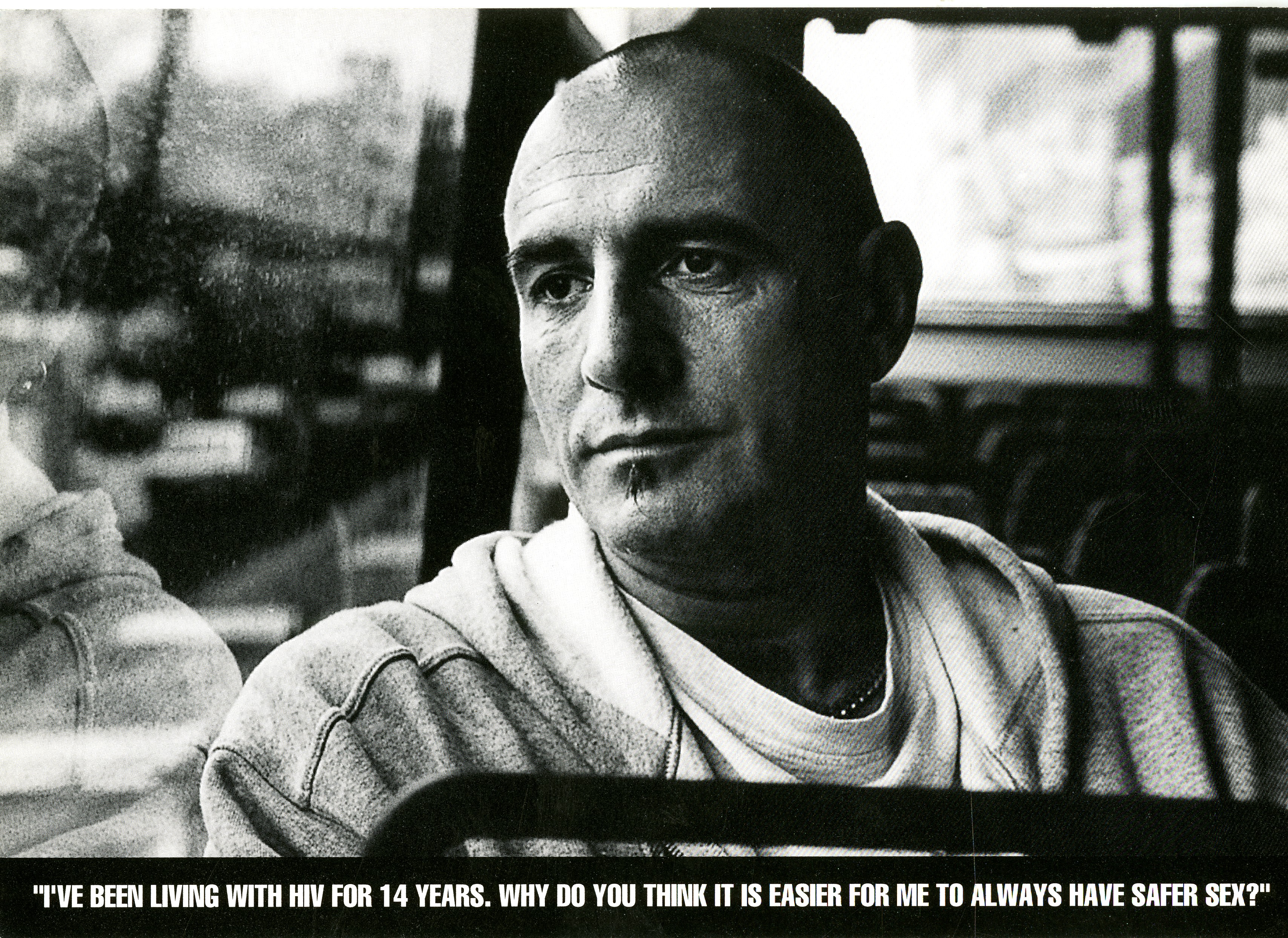

As part of my volunteering, I had the opportunity to appear in the charity’s Safer Sex campaign, the first out of home awareness campaign aimed at gay men. This took the charity’s message to the public, featuring in bus stops, billboards, and London Underground stations.

During those early years, though my CD4 count crashed to 200 in 1989, officially categorising me as having an AIDS diagnosis, but I refused treatment. I’d seen AZT trials injure people physically and emotionally; the drug’s toxicity was brutal.

For years I survived on prophylactic antibiotics, warding off infections like shingles and pneumonia. Then, in 1996, everything changed, when combination antiretroviral therapy became available. Within weeks, I felt 'Lazarus raised from the dead', I rebuilt a patio outside my bedroom as proof of newfound energy.

Since 1997, I’ve kept up my manageable, once-daily medications, which is nothing like the early drugs, they’re safer, more effective, and life-saving.

Learning I couldn’t pass on HIV sexually if I kept on my medication liberated me. The Can’t Pass It On campaign and messaging shared by Terrence Higgins Trust has been revolutionary

Then there’s PrEP, a game-changer for prevention. Where once condoms or abstinence were the only options, HIV-negative people can now take medication to stop HIV entering the body. Both prevention and effective medication together build the foundation for ending new cases of HIV.

But stigma hasn’t disappeared because of effective medication, it thrives in ignorance and fear. Even today, I’ve witnessed casual discrimination from healthcare and beyond.

Today, there have been many changes in the way that we’re fighting HIV – from the effectiveness of treatment people are living longer and can’t pass on HIV, awareness campaigns, legal protection under the Equality Act 2010, and coordinated attempts to end new cases of HIV by 2030.

But HIV stigma remains stubborn. I’ve volunteered for decades, and still people shy when I mention HIV. They don’t understand the scientific fact that people on effective treatment cannot pass on HIV through sexual contact. They’re scared. Not of the virus, but they’re scared of the label.

Now, I’m 76 now. I live in the same South London co-op I’ve called home for over 35 years. I tailor costumes. I volunteer. I garden. I swim in cold water. And I’ve been living with HIV for forty years. I do it all because I want everyone to see HIV not as a death sentence but as a manageable condition. I want everyone to see the progress from the early 1980s.